Finding the right balance between continuity and change can help leaders better manage the cultural changes that occur during a digital transformation.

Digital transformation transcends technology and business models. Organizational culture also plays a critical role in successfully leading an organization into the digital era; indeed, the success of a digital transformation relies on a deep understanding of the intricacies of culture. But few business leaders fully understand how a company’s culture changes during a digital transformation — and, more importantly, how it doesn’t change.

Consider the case of Maersk, the Danish shipping and integrated logistics company, which has been undergoing a significant digital transformation. Those efforts, which took off when Jim Hagemann Snabe became chairman of the board in 2016, entailed collaborating on blockchain with IBM and providing digital platforms to customers. Internal cultural tensions at Maersk became apparent late in 2021, when Søren Vind, a senior engineering manager and head of forecasting, had a public disagreement about the company’s identity with a veteran Maersk sea captain who serves as the employee representative on the board. In an interview with a Danish publication, Vind argued that Maersk “used to be an industrial company that had technology on [the] side” but had become “a technology company where we have some physical devices we need to move around.” Captain Thomas Lindegaard Madsen responded in a public LinkedIn post — subsequently edited to defuse his criticism — that read, “I am very sorry, but I will have to correct you.” Pointing out that the maritime business contributed 78% of group revenue and that the group has 12,000 seafarers, the captain declared, “We are NOT a tech company who ‘happens’ to operate ships.”

Of course, both the captain and the executive are right — and wrong — in their statements, which merely represent different perspectives on how digital transformation and culture interact. Where the IT executive views digital transformation from a cultural change lens, the sea captain views it from a cultural continuity lens. Both lenses are valid, both can coexist, and both need to be jointly managed for a transformation effort to thrive.

The Culture-Transformation Matrix

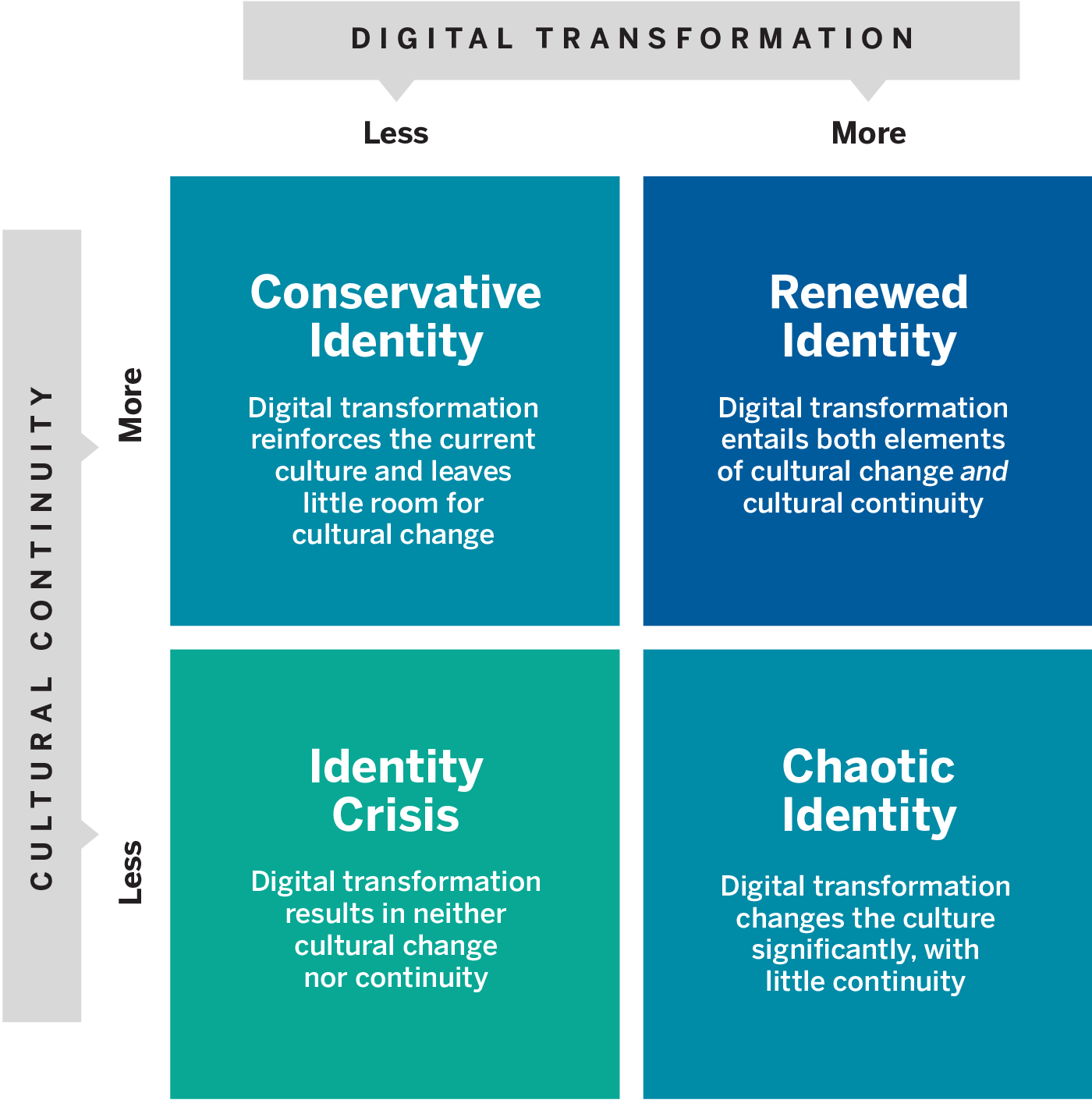

As the names imply, cultural change refers to how a digital transformation may alter an organization’s culture, and cultural continuity refers to elements of the culture that remain stable. In short, during any organizational transformation there’s always an interplay between cultural change and continuity as cultures evolve, but most digital transformation initiatives instead emphasize cultural change at the expense of cultural continuity. This is unfortunate, because it could end up being the root cause of a failed digital transformation. Change without continuity results in chaos, while continuity without change results in conservatism, as illustrated in the Culture-Transformation Matrix below.1 In other words, the right balance must be achieved.

The Culture-Transformation Matrix

Attention to the intricate cultural aspects of digital transformation can help balance cultural change and continuity.

Leaders should consider the interplay of cultural change and digital transformation, which in combination create the four elements of cultural identity represented in the matrix: identity crisis, chaotic identity, conservative identity, and renewed identity.

Identity crisis: If digital transformation results in neither cultural change nor continuity, the organization can be said to be in need of a corporate identity. Such an identity crisis makes transformation initiatives difficult, because the process is not grounded on a solid foundation. Of course, the organizations facing identity crises are unburdened by preexisting beliefs that could impede a digital transformation. The managerial imperative in such contexts may be to create a strong digital identity that incorporates digital technologies into the company’s business model and value propositions, and to create a culture where employees exhibit digital literacy and familiarity with AI, data science, and social media.

Many startups find themselves in this cell: They’re too new to have cultural continuity and too afraid of making grave mistakes to substantively engage in cultural change. The result is a passive and largely identity-less startup. For instance, it’s common for startups to need time to find their niche in a market — but finding that niche is often a costly process that also closes the door on other opportunities. Digital capabilities similarly require time and come at a cost. As a result, around 36% of small businesses in the U.S. don’t even have a website.

Chaotic identity: If digital transformation changes the culture significantly with little continuity, the end result will be chaos. Change necessitates a cultural basis from which to emerge; without such a basis, the resultant change will likely be too fragmented and detached to make sense to members of the organization. Unfortunately, many digital transformations fall into this category, when executives create the narrative that the organization needs to urgently change and that the ways of doing business up until now should be abandoned altogether. Consequently, digital transformations often fail by having too much change and too little consistency.

The Hershey Co. has experienced its share of unsuccessful transformation projects, such as an enterprise resource planning implementation that failed due to a rushed process with too many systems deployed at once. But from these failures, the company learned to create a successful digital strategy, as noted by chief digital officer Doug Straton: “The biggest component of digital transformation is the cultural change that goes along with it. It’s good to have a strategy and technology that will enable it, but the hardest work is around culture, reeducation and the upscaling of the organization.” While this is undoubtedly true, successful digital transformation requires some level of cultural continuity in order to avoid the chaos of an organizational identity detached from its historical past.

Conservative identity: If digital transformation reinforces the current culture and leaves little room for cultural change, the end result will likely be cultural dogma and inertia. In other words, the organizational culture can obscure the organization’s recognition of its own outdatedness, creating the risk that the organization will become obsolete. In such a scenario, the collective culture draws upon a snapshot of the past — which, in a fast-moving digital world, will likely result in an unfortunate path or even a potential trap, as exemplified by the fates of companies like Kodak, Blockbuster, and Nokia.

Nokia had a strong cultural belief in its own core strengths of product functionality and a device-centric operating system, but it overlooked the move toward software, platforms, and ecosystems made by competitor Apple, which showcased its groundbreaking iPhone device and iTunes and App Store platforms. Nokia had initially become a market leader due to its innovative device technology, so it continued to repeat what had worked in the past — until it became painfully clear that it had missed the market shift from devices to platforms, essentially rendering the company a sitting duck. Ultimately, Nokia lost out to Apple due in part to its conservatism — an overreliance on cultural consistency at the expense of cultural change.

Renewed identity: A digital transformation entailing both elements of cultural change and cultural continuity allows for the kind of sustainable renewal that can secure corporate longevity. While some elements will change and adapt to a new digital reality, those change initiatives are sufficiently rooted in the preexisting culture to ensure cultural continuity as well. The end result is a digital transformation that operates in accordance with the experience and understanding of organizational members. This may result in a slower but more successful transformation.

For instance, when The New York Times initially sought to navigate the digital landscape, the publication created a system to tag digital content that aligned with its existing extensive index — which had given the paper a competitive edge with libraries and researchers a century earlier. New digital features meshed with more traditional elements, highlighting cultural continuity despite modernization.

Another example of such renewal can be seen at IBM. Founded in 1911, IBM’s long history and traditions manifest in a strong corporate culture characterized by professionalism, reliability, and technological innovation. IBM has stayed at the forefront of multiple technological waves and transformed itself to adapt to a market that has evolved from early computing to the internet era of digital services, blockchain, and AI. It has successfully and continually changed its business model to align with technological developments, adapting its culture — for example, by creating a service emphasis to support its service business — while simultaneously maintaining the core cultural values on which it was founded. As the company’s second president, Thomas Watson Jr., put it, “Be willing to change everything but who you are.”

Using the Culture-Transformation Matrix

The matrix provides a language for understanding the cultural dynamics at play in digital transformations. Applying the matrix can help us to better analyze and explain the previously discussed example of Maersk, for instance. The IT executive at Maersk represented chaos and the sea captain conservatism — opposing ends of a continuum — but the very fact that both men held senior positions shows that Maersk has every opportunity to reach the renewed identity cell in the matrix. Maersk’s organizational aim of “integrated end-to-end logistics” encompasses both perspectives; to achieve it, the company needs to make cultural changes toward becoming more technology-driven in order to deliver customers an integrated solution, but it can’t make this shift without maintaining its cultural backbone and established offerings of end-to-end logistics.

If leaders’ views of cultural change and continuity are expressed and concerns are addressed in a respectful tone, then there is a home for both perspectives in the digital transformation. Such cultural inclusion is the cornerstone of the renewed identity cell in the matrix. Managers must demonstrate both their openness to change and respect for the existing culture. Moreover, they need to be explicit about which parts of the culture might change and which parts should remain stable, while emphasizing how this cultural shift will affect the core identity of the organization.

While digital transformation refers to how digital technologies change business models, people and cultural concerns must remain front and center. By identifying the relevant cultural dynamics and exposing the related internal concerns, the Culture-Transformation Matrix tool can eliminate the danger of overlooking critical cultural concerns. As a result, managers can more deliberately start to manage the human aspect of business transformations in a thoughtful way. Taking the intricate cultural aspects of digital transformation into account might prevent your company’s digital transformation from becoming another failed initiative — and increases the odds of it becoming a success story heralded by the popular press. Ultimately, digital transformation is also a cultural transformation.

REFERENCES (1)

1. For related work on strategies entailing continuity and change, see D. Ravasi and M. Schultz, “Responding to Organizational Identity Threats: Exploring the Role of Organizational Culture,” Academy of Management Journal 49, no. 3 (June 2006): 433-458; S. Nasim and Sushil, “Revisiting Organizational Change: Exploring the Paradox of Managing Continuity and Change,” Journal of Change Management 11, no. 2 (June 2011): 185-206; S. Nasim and Sushil, “Flexible Strategy Framework for Managing Continuity and Change in E-Government,” in “The Flexible Enterprise,” eds. Sushil and E.A. Stohr (Delhi: Springer India, 2014), 47-66; and Sushil, “A Flexible Strategy Framework for Managing Continuity and Change,” International Journal of Global Business and Competitiveness 1, no. 1 (2005): 22-32.

Comments

“I fear the day that technology will surpass our human interaction. The world will have a generation of idiots”.

“It’s become appallingly clear that our technology has surpassed our humanity”.

Albert Einstein