We can achieve the rewards of reflection and avoid the pitfalls of rumination by

having a plan to direct our energy.

The neuroscience is clear: Our brains are capable of processing only a fraction of the information available to them, and we have a fixed amount of mental energy at our disposal, regardless of how much we want or need in any given moment. Consequently, our brains use as little mental energy as possible whenever possible. It isn’t laziness — it’s fuel efficiency.

The bottom line is that there is a limit to how much thinking we can do and how much energy is available to us on any given day, so it’s essential that we spend our precious mental energy deliberately and thoughtfully. We can’t afford to waste it on things that serve to distract and deplete us in harmful ways.

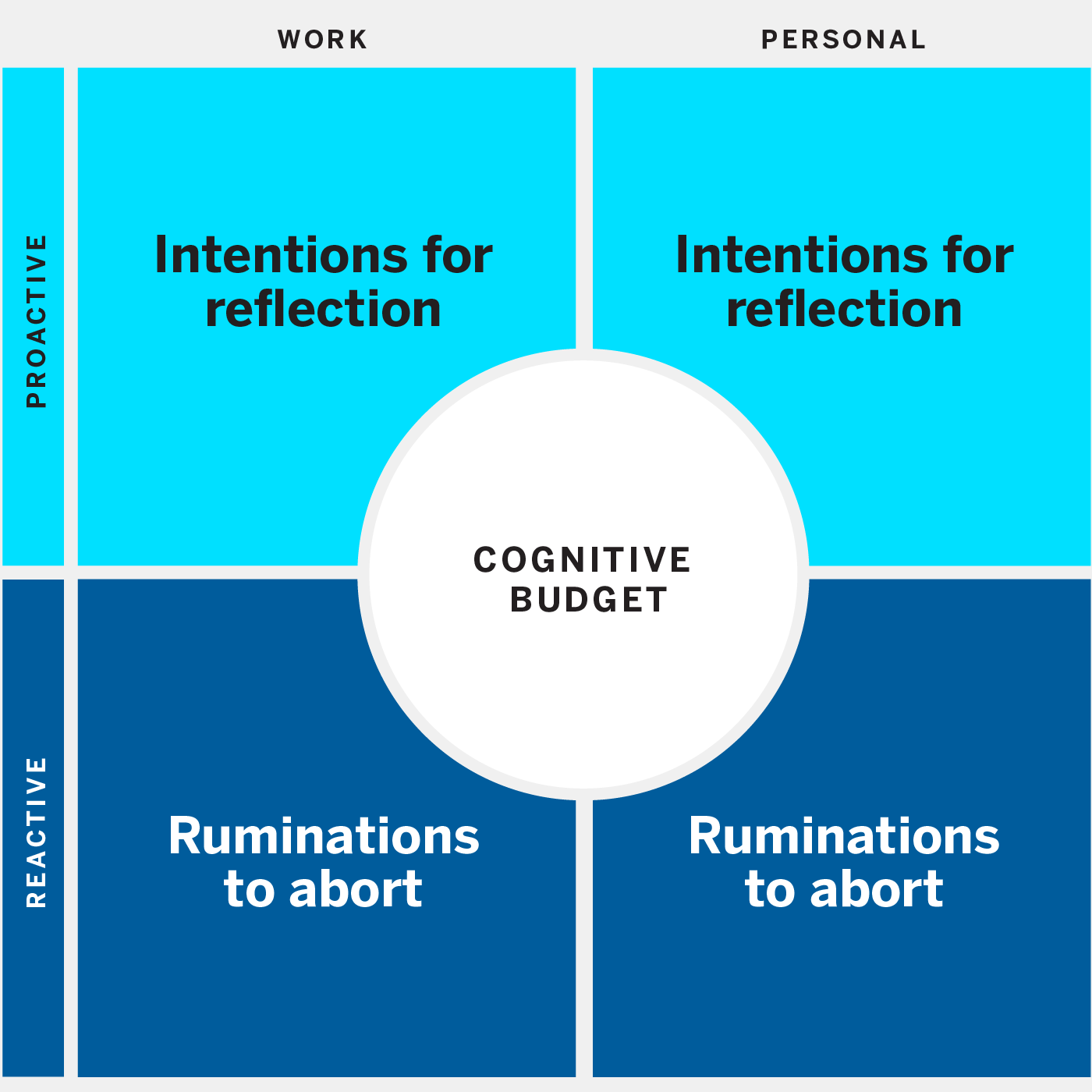

So, what’s a good approach to avoid wasting our finite energy on that which doesn’t serve us? A budget, of course, to forecast resources, estimate need, and create a plan for future decision-making. But for our minds? A “cognitive budget” is hardly a natural pairing of concepts. Our days are unpredictable, and our brains don’t work like spreadsheets, so a cognitive budget will necessarily be sloppy. But creating one, and revisiting it often, allows us to enact proactive and reactive strategies that leave us happier with more effective minds.

Unconscious and Conscious Thinking

Our unconscious minds play a much larger role in our lives than many of us realize, including helping to protect us emotionally and functionally from the challenges of everyday life — from debilitatingly painful feelings to massive information overload. In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, psychologist and behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman describes two types of thinking that provide a conceptual understanding of unconscious behavior. System 1 thinking is easy, fast, intuitive, and emotional. System 2 thinking is hard, slow, intentional, and logical. Compare the act of driving home from work (System 1) with driving somewhere you’ve never been before without using a GPS (System 2). One takes a lot more work than the other.

We have only so much System 2 thinking available over the course of the day, so we naturally spend as much time in System 1 thinking as possible. (Many studies indicate that 90% to 95% of our decisions are made unconsciously.)

The problem is that our unconscious minds often keep us from thinking about what’s good for us and drive us to think about what’s not good for us. Because the purpose of the cognitive budget is to keep our focus on the things that serve us well, it needs to be both proactive and reactive: proactive in budgeting the limited currency of System 2 thinking, and reactive in responding to our unconscious minds, which too often lead us toward counterproductive thinking. The proactive and reactive halves of our cognitive budgets are represented by the types of thinking they seek and avoid: reflection and rumination, respectively.

Budgeting for Reflection — and Avoiding Rumination

Reflection is the hero of our story. It is the most valuable type of thinking we can do, because we get the greatest return on investment of mental energy from it. Reflective thinking gains us access to the very best of our minds, from the remarkable (our genius) to the meaningful (our compassion, empathy, forgiveness, and capacity for joy). It may be hard work, but reflection enables all the rewards that make the hard stuff in life worth it.

There are several key components of reflection, but humility is essential. Reflection is thinking without an agenda. If we lack humility, we have an agenda — to protect and enhance our self-image. But if we don’t consider ourselves infallible or feel defined by any position we’ve taken or belief we’ve held — in other words, if we have humility — then we don’t feel threatened by considering conflicting perspectives or reevaluating our beliefs. Humility kickstarts a virtuous cycle: By helping us articulate vulnerabilities, it enables us to go wherever our thoughts take us, even if they are uncomfortable or challenging. (Adam Grant’s wonderful book Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know, which examines the benefits of learning to question our opinions, is a testament to this very idea.)

Rumination, on the other hand, is the primary antagonist of the cognitive budget. Psychologist Amy Summerville describes rumination as the thinking that provides no further “nourishment,” metaphorically comparing it to cows’ repetitive cycle of chewing, swallowing, regurgitating, and rechewing their food. When humans ruminate, we replay events repeatedly in our minds without gleaning insights or progressing. Rumination eats up mental energy that could have otherwise been spent on something worthwhile and provides nothing but suffering. Rumination hurts us immensely, so the cognitive budget aims to help us to do less of it.

Unfortunately, most of us cannot simply stop rumination from happening — at least, not in the short term. Our unconscious minds take us there without our consent. But we can learn to identify when we are ruminating and put a stop to it. This approach lies at the heart of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which posits that our beliefs about triggering events, rather than the events themselves, are the cause of most of our emotional and behavioral challenges. Changing how we think in those moments can transform our effectiveness and how we experience life.

(Important note: It is imperative that we do not use the idea of avoiding rumination as an excuse to avoid reflecting on the hard stuff. That’s repression, and it is unproductive and even worse than rumination. The difference between reflecting on hard stuff and ruminating is that ruminating never leads to any new ideas, new behaviors, or a sense of resolution.)

Creating Your Work Cognitive Budget

The cognitive budget aims to help you do two specific things: proactively direct your mental energy where you do want it to go (reflection) and stop your mental energy from reactively going where you don’t (rumination). Because our minds are unpredictable, the cognitive budget is less a map than a compass, incorporating elements of positive psychology (writing down intentions), behavioral economics (nudges), and CBT (cognitive restructuring).

Any approach that helps you to be more intentional with your mental energy is a huge win. Many people will benefit from a budget that separates work and personal concerns to make each more manageable. (This also can keep you from thinking about work when you’re not working, if that’s a challenge for you.) I’ll focus here on the work side, but budgeting for both areas has the potential to be immensely valuable.

Cognitive Budget Template

Creating a cognitive budget is a good way to be more intentional with your mental energy.

The first rule of the cognitive budget is that it’s yours. Whatever works for you is what’s right. How you complete this table will determine the extent to which the cognitive budget is helpful to you. You’ll use your reflections and ruminations sections differently, so we’ll go through them separately.

There are many ways to express intentions for reflection for your work life. They can be specific questions, like “Why is the team struggling to collaborate?” or “Why does the team work together so well?”; in the form of general subjects, like “professional development” or “career advancement.”; or as general directions, like “Figure out the product backlog” or “Improve click-through rates.”

Identifying ruminations to abort is trickier, but they’re absolutely worth articulating so that you’ll recognize them more readily when they emerge. You can surface ruminations by asking some hard questions: What do you think about that makes you feel worse the longer you think about it? To what topic do you consistently return without making any progress toward a solution or a sense of resolution? What painful moments from your past do you relive repeatedly without getting anything out of it? The better you can articulate these answers, the easier it will be to recognize those thoughts when they’re surfacing.

Remember that the cognitive budget is messy and contextual, so try not to get too caught up in the wording — the underlying ideas are what matter. You are reminding your future self that there are the subjects you do and do not want to spend time thinking about. Any combination of words or sentence structures that accomplish that is perfect.

Reflections at Work

What subjects for reflection will have the best results for our careers? Of course, it depends on the person doing the thinking, but the following are helpful categories when considering your work life.

- Mission: Identifying what you care about, increasing time spent doing it, finding ways to do more

- Growth: Acquiring skills, adding value, advancing career

- Interpersonal relationships: Building relationships, improving dynamics, nurturing connections

- Strategy: Identifying problems, forecasting conditions, surfacing connections

- Operations: Improving efficiency, driving effectiveness, prioritizing measurement

- Innovation: Driving ideation, improving implementation, creating value

- Customers: Increasing satisfaction, supporting retention, driving engagement

- Marketing: Updating value proposition, iterating messaging, promoting untraditionally

- Support: Providing interpersonal, departmental, organizational resources

As you read this list, pay attention to what enters your mind regarding your work life and write it down. Revisit the list again tomorrow, and again in two weeks.

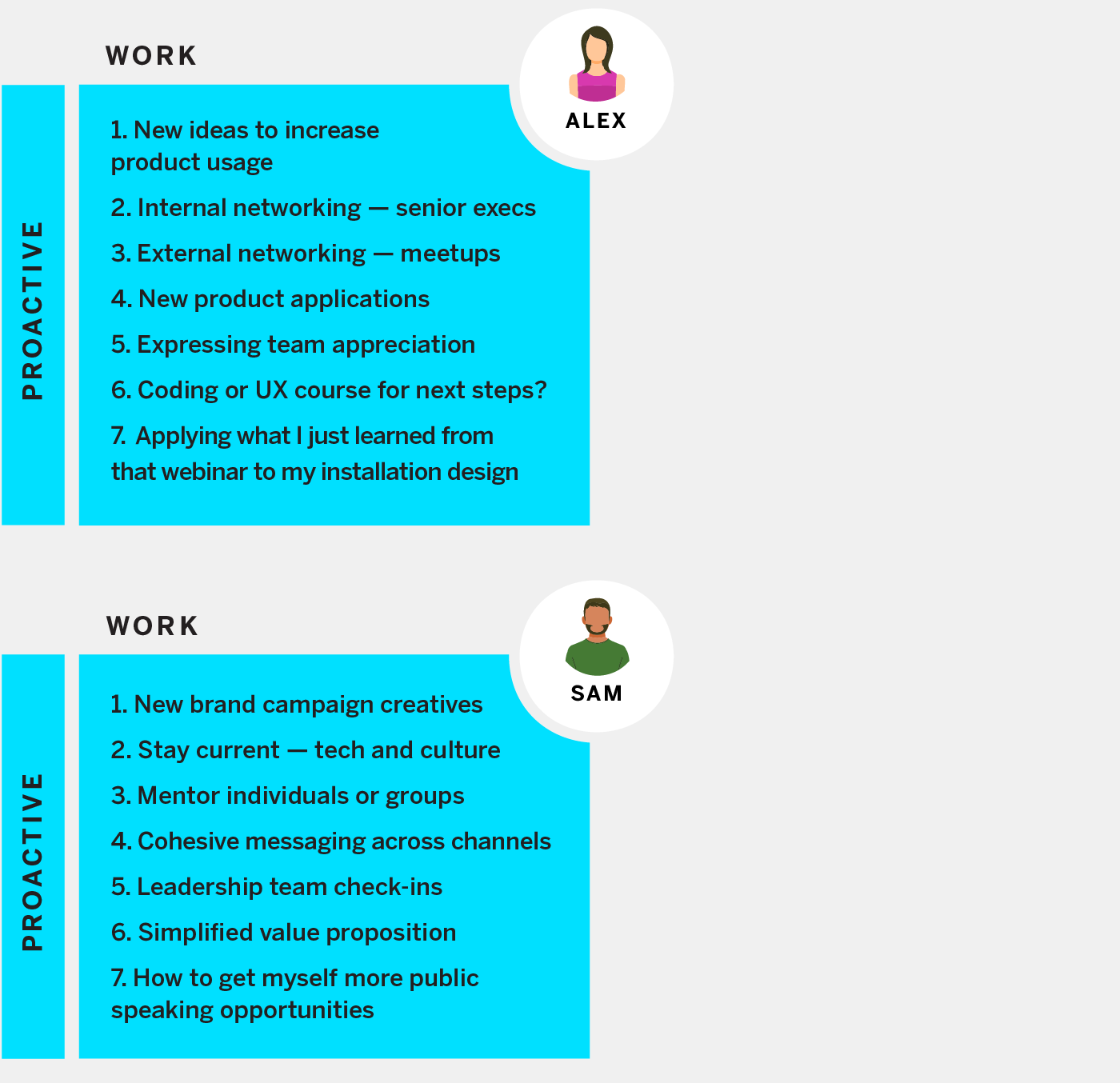

Let’s look at two hypothetical examples. Alex is early in her career in software product management, and Sam is established in his career in marketing. For now, we’ll focus just on the proactive (reflection) work column; we’ll address the personal column later.

Reflections at Work

This hypothetical cognitive budget shows the proactive, or reflective, work column.

Thinking about these things more intentionally will lead Alex and Sam to insight and action, making both more effective in their careers. But you may notice that Alex and Sam are individual contributors.

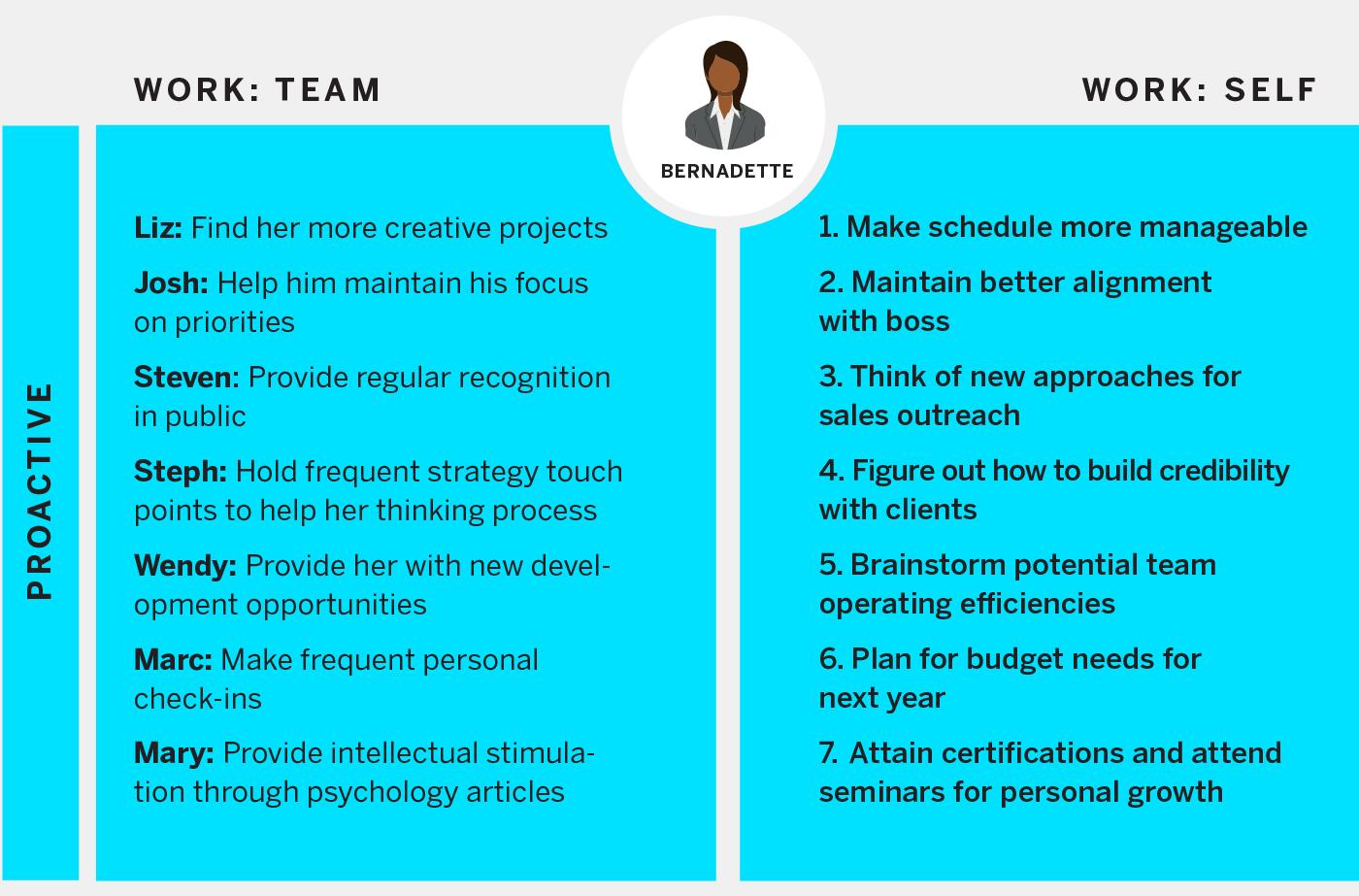

What would a cognitive budget for leaders look like? Most managers already have impossibly full plates before they even get around to engaging with their people. And yet their No. 1 priority ought to be getting the most from their teams. A cognitive budget can focus their attention where it belongs — on the team first. What are your team members’ needs? What actions can you take to support them? And how are they doing right now?

Let’s use Bernadette, a hypothetical manager of seven direct reports, as an example. Note that she includes all seven reports — as well as herself — in her budget.

A Leader’s Cognitive Budget

A hypothetical manager, Bernadette, includes herself in addition to her direct reports in her cognitive budget.

Of course, the needs of Bernadette’s team may change as often as her own. Bernadette would do well to regularly take the pulse of each team member and devote enough mental energy to ensure that she is getting the most from each person. Given that employees need to be recognized at least once a week in order to remain engaged, managers ought to check their budgets weekly and update them as needed.

Ruminations at Work

“I cannot believe I actually said that. I am such an idiot. There goes my career.” Sound familiar? The good news is that with experience comes the knowledge that only rarely does anything come of such worries. The bad news is that knowledge doesn’t prevent us from freaking out — and those freak-outs are costly. Research shows that work-related rumination meaningfully hurts people’s performance in important ways, including their memory and their ability to start or finish projects.

While work-related ruminations are intensely personal, there are likely a few main sources for all of us.

- Exclusion: Being left out of meetings, consideration, decision-making

- Organizational politics: Addressing toxicity, conflict, power dynamics

- Disappointment: Missing out on promotions, assignments, deals

- Disrespect: Combating belittling, bullying, dismissing

- Task management: Managing deadlines, volume, status

- Fairness: Dealing with unfair treatment, rewards, consequences

- Interpersonal relationships: Navigating collaborations, lack of support, incivility

- Insecurity: Facing imposter syndrome, low self-efficacy

Write your ruminations out, just for you. They’re not meant to be shared.

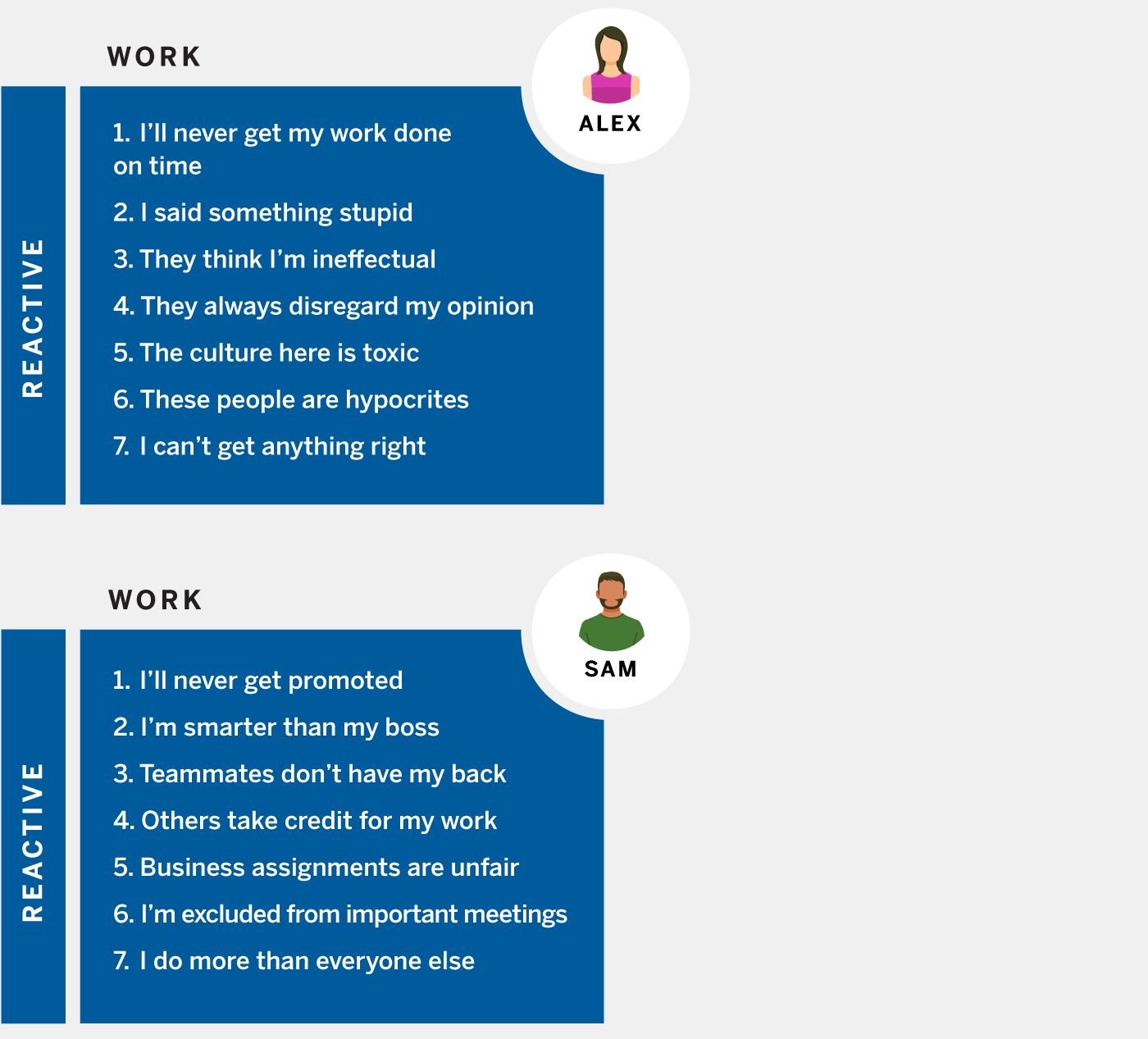

Let’s revisit Alex’s and Sam’s budgets to look at how they define their workplace ruminations.

Workplace Ruminations of Two Individual Contributors

The goal of including your unique ruminations in your cognitive budget is to prepare yourself to recognize rumination in the moment.

Addressing Rumination

Addressing Rumination

We have to build off-ramps from the rumination trap, which offers no natural exits. Becoming aware of when you are engaged in destructive or unproductive thinking and then consciously shifting your focus to something productive is nothing short of life-changing — and, admittedly, a lot easier said than done. But knowledge — or, in this case, awareness — is most definitely power. With a cognitive budget, we’re primed to better recognize rumination when it happens, and to do something about it.

The goal of including your unique ruminations in your budget is to prepare yourself to recognize rumination in the moment. With this awareness, you can change your focus. If using sheer willpower to redirect your thoughts isn’t possible, try asking yourself CBT-based questions: What is the evidence for or against this idea? Am I taking selected examples out of context? Are my judgments based on feelings rather than facts? Leaning in to logic and broader perspectives can help abort unconsciously driven rumination. (If you find that you cannot stop your ruminations on your own, you may want to seek professional help from a cognitive behavioral therapist.)

Again, it’s critical to note that the goal is not to ignore the subjects of your rumination. Addressing rumination means acting or finding closure. The only unacceptable outcome is continued ruminating.

For each of their ruminative statements, Alex and Sam must consider whether these are rational or irrational beliefs. Is it actually true that Sam will never get promoted, or is that an exaggerated belief? If the former, he has a decision to make: whether that is enough reason to look for another job. If the latter, then for his own well-being, Sam needs to train his mind not to dwell in negative exaggerations — which, with CBT techniques, is far more doable than it may sound.

Creating Your Personal Cognitive Budget

When it comes to creating cognitive budgets for our work lives, we can rely on some basic categories to capture most of the relevant content we’re looking for. But when it comes to our personal lives, the possibilities are infinite. For some, social connections will be at the top of the list; for others, personal growth. Some will seek to confront deeply rooted emotional pain, while others will seek to maximize joy in the present. And what’s true today may not be true tomorrow.

Fortunately, there is no right or wrong way to do this. Whether a topic is challenging or enjoyable, the only criterion for reflection is that it be worthy of your focus. A good place to start is, “What do you want to think about? What makes you happy? What do you want to improve?” A quick search on questions for reflection or a brief review of Maslow’s theory of self-actualization will give you more than you need to get started.

Identifying personal ruminations is also much more difficult than work ruminations, again because the breadth of topics is so vast, including your entire past and future. The ruminations I’m currently addressing look very different from those that occupied my mind 10 years ago; the same might be true for you.

As for aborting your ruminations and getting yourself unstuck, I can promise this: The more you practice, the easier it will get. The good news is that identifying the ruminations you want to let go of is an incredible start.

Best Practices for Budgeting

So you’ve written out your first ever cognitive budget. Congratulations! But there’s one last thing to do: Nudge yourself. Nudging is a behavioral economics practice stemming from the idea that sending yourself reminders through multiple channels makes them harder to ignore. Here are some possible approaches.

Make your budget visible. Whether it’s a business-card-sized printout taped to your keyboard, a sticky note on your desk, or an image on your screen, put your budget where it will be persistently visible to you. (If it’s visible to other people, for privacy you can use generalized words, like “development” instead of “evaluate coding versus UX for future coursework.”) Out of sight can in fact mean out of mind, so keep your workplace and personal budgets anyplace you are going to see them.

Incorporate your budget into your daily routine. Get into the habit of reading your budget in full before your commute. This is prime reflecting time. (But drive carefully!) And if you’re working from home, schedule a few walks around the block during which you can check your budget.

Schedule a few five-minute reflection sessions each day on your calendar. (And don’t blow them off, even when you are very busy.) You can either skim your budget in the moment or be very specific on your calendar regarding what to think about and when. Separately, schedule a few alarms on your phone each day to remind you to check your budget — and don’t turn them off until you are actually looking at it. Alternatively, schedule a few push reminders each day that prompt you to reflect on a workplace budget item. (Even getting a push notification with a word like “development” will help foster reflection.) For your personal reflections, time the nudges outside of work hours.

Keep your budget fresh. Finally, your budget will inevitably lose potency over time, so it is important to update it frequently. You may achieve a goal, experience new life circumstances, or simply evolve to prioritize different things. But most importantly, it is crucial to update your budget the moment it becomes stale. You can tell it’s stale when the words no longer spark any thought.

There is good reason to be confident that the cognitive budget will work for you, because it combines data-validated techniques that work from positive psychology, cognitive behavioral therapy, and behavioral economics. Metaphorically speaking, when you combine whipped cream and hot fudge with ice cream, you know it’s going to taste good. May your cognitive budget serve you as well as mine has served me.

Comments